The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks by Brooklyn College’s Distinguished Professor of Political Science Jeanne Theoharis is a readable and fascinating account of the life of Rosa Parks that won many awards when it was punished in 2013. Here’s my “take” on the story, based on the book. I link to other summaries and reviews below.

Even days after her arrest for refusing to move on a Montgomery bus, the real Rosa McCauley Parks was treated as a voiceless symbol while the men planned rallies and made the speeches and other women (of the Women’s Political Council) organized the boycott without consulting her. Contrary to the public construction of Mrs. Parks as an apolitical tired old lady whose feet ached who unwittingly changed America, Mrs. Parks was a seasoned and highly respected political organizer. At the time of her December 1955 arrest, Mrs. Parks had already been elected to statewide office in the NAACP as its secretary and had logged a decade of work defending victims of White violence. In the years immediately preceding her arrest, Mrs. Parks had been the organizer of the Youth Council of Montgomery’s NAACP. She had attempted unsuccessfully to mobilize a community response in support of Claudette Colvin, a 15-year-old member of the NAACP Youth Council, who had been arrested and beaten half a year earlier for refusing to move off a Montgomery bus, as well as providing personal support to Colvin when nobody else did. She was politically militant but spoke softly and was very reserved in front of most White people, whom she did not trust. She had expressed discouragement about the failure of Montgomery’s Black community to mobilize collectively.

Mrs. Parks did not expect community support when she refused to move, and had good reason to fear violent retaliation for her act. All the other Black people asked to move at the same time had complied, even though the request for them to give up their seats on a full bus violated Montgomery’s bus segregation ordinance. Mrs. Parks was chosen as the test case for a boycott and lawsuit not just because of her respectability, but also because she was well known in the community. A boycott was organized to be held on the day of her arraignment by the Women’s Political Council, a middle class Black organization, and Black ministers, without consulting Mrs. Parks. She was on the platform at the huge community meeting after the first day of the boycott, but was not invited to speak and told by the men that she had nothing to say beyond the fact of her action.

Theoharis attributes the MIA’s silencing of Mrs. Parks to several factors including gender bias, class bias, and fears of red-baiting. Many writers have discussed gender issues and the ways in which women were the organizing backbone of the Civil Rights Movement but the public limelight was dominated by men. Theoharis also lifts up class bias and the way in which the college-educated ministers and members of the Women’s Political Council assumed that they should be the leaders and acted as if working class people had no political ideas of their own. Mrs. Parks, a skilled tailor who has come down in history with the title “seamstress,” had been unable to go to college due to needing to work to support her ailing mother, but she had been an avid reader from childhood and was well versed in Black history and Black political issues. Finally, Mrs. Parks and her husband Raymond had worked politically with Communist and left-leaning organizations, especially around the Scottsboro Boys case. Mrs. Parks was friends with some White radicals, especially Virginia Durr, who had arranged for her to be invited to the Highlander Folk School. Mrs. Parks and E.D. Nixon were militant members of the NAACP whose actions and proposals were sometimes opposed by more conservative NAACP members. Southern states, including Alabama, had banned the NAACP as a Communist organization and had fired teachers and others who were members of the NAACP. White Southerners claimed that Mrs. Parks was an outside NAACP agitator who had recently moved to Montgomery for the purpose of staging her arrest. Mrs. Parks resigned from the NAACP shortly after the boycott began as part of a successful effort to distance her from the NAACP. Although the claims that she was an outsider and that her arrest had been planned by the NAACP were false, Mrs. Parks was a militant NAACP activist who had previously been involved in a bus protest. Interestingly, the effort to de-politcize the symbolic Rosa Parks worked, and the false apolitical image got national traction instead of the partially true White Southern version.

Mrs. Parks was surprised and happy when she saw the community mobilizing, and joined in the work. During the boycott, she worked on organizing transportation in Montgomery and also traveled and made speeches around the country that raised thousands of dollars for both the Montgomery Improvement Association and the NAACP. Unlike some others who made the fundraising circuit, she never took a cut for herself. This fed into her financial crisis and subsequent ill health.

Both Rosa and her husband Raymond were let go from their jobs shortly after the boycott began and could not get jobs from Montgomery’s White employers. Despite their destitution and activist backgrounds, neither was ever hired by either the MIA or the NAACP, although other community members, generally those from middle class backgrounds, were hired for staff positions. The Parks household received daily death threats and abusive telephone calls. Raymond Parks, a barber by trade, who himself had several decades’ experience as a militant organizer, became the primary caregiver for Rosa’s ailing mother, who lived with them, and suffered a mental breakdown from the stress of their poverty and ongoing threats of violence.

Two years after the boycott, still unemployed and poor and both in ill health stemming from stress-related diseases (Rosa was hospitalized for ulcers), Rosa and Raymond Parks relocated to Detroit, where Rosa’s brother lived, along with Rosa’s mother. It was several years before either Rosa or Raymond were physically able to work. Rosa lived in a poor Black part of Detroit near the epicenter of the 1968 Detroit riot until her death in 2005. Their neglect by both the MIA and the NAACP became something of a scandal in Black circles, as each organization blamed the other, and there were periodic fundraising drives among Black and White radical organizations to pay their hospital bills and remediate the threat of starvation. The Parks’s financial situation did not stabilize until Rosa Parks was hired in 1965 to be a Detroit office staff member by newly-elected Congressman John Conyers, a position she held for many years.

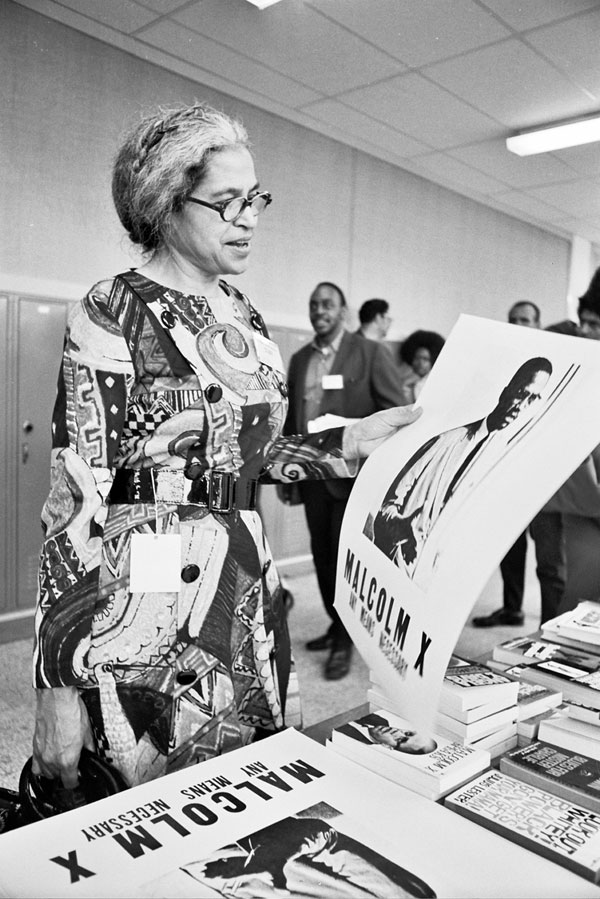

Mrs. Parks continued her support of militant activism after moving to Detroit. She continued to accept invitations to travel all around the country to show up and lend support to Black causes. The archives of her papers and interviews with her friends and acquaintances reveal that she attended many meetings of militant Black organizations, including the Republic of New Africa, and was part of a circle of militant Black people in Detroit. She always admired Martin Luther King, Jr. but did not share his complete belief in nonviolence. Her family had a gun when she was growing up and she recalled her father sitting up on the porch with his gun when the KKK was active. She asserted the right of self- defense and stated that her position was close to that of Malcolm X, whom she had met several times and admired. She attended and spoke at the Million Man March. She subscribed to many Black publications and was well-read and well-informed about political issues. In her youth, she read Black history and felt that it was important for people to know their history. She cooperated with a biography oriented toward young readers. Consistent with her earlier years as an organizer of the NAACP Youth Council, she was not an old fogey who decried the youth, but showed up and was supportive of young activists. She was not particularly optimistic about the prospects for social change but felt that there was a moral duty to keep standing up and continuing to resist oppression. She did not advocate violent rebellion but she understood why some people did. Rather than hewing to one ideological line, in her actions, Rosa Parks implied support for the overall unity of the Black struggle in its diverse manifestations.

Mrs. Parks was interviewed often by both Black and White reporters, but they usually wanted to rehash the events in Montgomery and almost never treated her as the well-read and experienced political activist and political thinker that she was. She was rarely asked to comment on current events or struggles. She both resigned herself to being treated as a symbol of the past struggle and complained about it. She enjoyed watching schoolchildren act out her bus resistance and believed in the importance of teaching and inspiring young people, but she criticized the way most people thought she had stopped existing or thinking after that event. She rejected the frequent attempts to contrast her supposed quiet apolitical dignity with the brash trouble-making or undisciplined young militant activists. When she was mugged in her own apartment in 1994 by a Black youth, she said she prayed for him “and the conditions that made him this way” and rejected the dominant media’s portrayal of the event as signaling the dysfunction of the Black community.

The real Rosa Parks is a woman who persisted in the face of extreme adversity, who never stopped resisting, who showed up and stood up over and over throughout her life, and who saw herself not as some individualistic icon but as a part of an ongoing collective struggle that would continue despite setbacks. The real Rosa Parks is a true inspiration to us all.

“The Struggle Continues…The Struggle Continues…The Struggle Continues” an elderly Rosa Parks wrote over and over on a drugstore bag.

I listened to the Audible version that included an updated introduction that was written in 2015 about the contents of an archive of Parks’s papers that was not opened to scholars until after the book was published. This updated introduction provides an overview of how the new information from the archive reflects on the arguments in the book. I also purchased the Kindle version to use as a reference. To my disappointment, the Kindle version has only the older introduction and lacks this information.

There is also a really excellent multimedia web site based on this book that is intended as a resource for teaching about Rosa Parks. It displays the key points of history in screen-size short stories, and includes many pictures as well as links to videos and primary documents.

Additional sources:

New York Times book review by Nell Irvin Painter (March 29, 2013)

Review in Race & Class (2014 vol 55 issue 3 pp. 93-98) that summarizes the book by Victoria Birttain (link requires a UW Madison login)

Washington Post article by Theoharis summarizing the book Citation: “How history got the Rosa Parks Story Wrong”. Jeanne Theoharis. Washington Post December 1 2015.

https://rosaparksbiography.org/ is a site based on the Theoharis book that is organized for teaching. It includes many screen-sized histories of important events and additional multimedia sources.

6 comments